The Beginning

Some anthropologists and archaeologists believe that humans lived continuously in the region that we now call the Teche-Vermilion basin for at least five thousand years, and perhaps much longer (Cheramie, 2013). On the banks of Bayou Vermilion near Paul Breaux Middle School (originally Paul Breaux High School) there was a freshwater spring called Chargois Springs (Figure 1) which supported a large Native American settlement. Griffin (1959) reports that for a long time, students of Paul Breaux High School "turned in to the principal after every good rain arrowheads and pieces of pottery that were on the school grounds."

Findings strongly support the hypothesis that native Americans lived at the Chargois Springs in relatively large numbers for a very long time (Cheramie, 2013). The Chargois Spring was probably a Native American meeting place where trade of all kinds took place. The availability of clear cool fresh water, in combination with its location on a ridge between the Atchafalaya Basin to the east and the prairies to the west would have made this an ideal habitation site. Evidence of long-term habitation suggests that the Chargois Springs was fed by a stable free-flowing

artesian aquifer, the Chicot Aquifer, for centuries if not millennia prior to the coming of European colonists.

The Chargois Springs were the location of many picnics reported in

lafayette newspapers before 1900. Soon after the 1927 flood, Chargois Spring ceased to flow, and while some attributed this to river sediment sealing the spring, it is more likely that dredging of the Vermilion River next to the spring cut through the clay confining layer which maintained pressure within the Chicot Aquifer which fed the spring. The resulting loss of pressure would have caused the formerly free-flowing spring to stop flowing. Griffin reports that in the 1950's the place still bore the name Chargois Springs and older Lafayette residents fondly recalled bathing there when the water still flowed.

|

Figure 1. Photo from Griffin (1959): "A Picnic at Chargois Springs about 1898. The back row: George Bailey, (2) Anita Hohorst (Mrs. J. Franklin Mouton), (3) J. Alfred Mouton, (4) Stella Raney, (5) Neveu, (6 ) Alix Judice (Mrs. J. Alfred Mouton) with guitar, (7) Ned Mouton (brother of Vavaseur), (8) Louise Judice (sister of Alix Judice), (9) Dr. Gabriel Salles (Josette Salles' brother), (10) Frank Moss. Sitting: (1) Florian Cornay, (2) ?, (3) Albert Judice (brother of Louise and Alix Judice), (4) Martha Mouton (back), (5) Marie Revillion (front Mrs. Marsh), (6) Felix Salles (front), (7) Sidney Mouton (back), (8) Emily Moss (Mrs. George deBlanc), (9) Johnny LeBesque (end). "Souvnir offert a Stella Trahan (the daughter of Dr. Trahan) par un ami sincere et devoue, Sidney Mouton," is written on the back of this photograph."

|

Today, the combined impacts of pumping for irrigation and municipal uses, excavation, and dredging have reduced pressure within the aquifer from a state of positive pressure and free flow, to a negative pressure now measured as static well water elevation roughly 50 feet below surface in Lafayette (see, for example, Figure 6,

Waldon, 2017a). Chargois Spring now serves as a reminder of how failure to consider the consequences of our actions can lead to unanticipated destruction of what could have been a sustainable resource for ourselves and our children.

|

Figure 2. Ad from the Lafayette

Advertiser, Dec. 8, 1900. |

Throughout most of the 19th century, Lafayette residents had to rely on either rain fed

cisterns (Figure 2), surface water, local springs, or numerous individual wells to provide for their domestic water needs. Shallow domestic wells for drinking water were associated with risks to health because of contamination from the surface, and citizens preferred drinking water from cisterns (Lafayette Advertiser, 1897). Deep wells were considered a low health risk because water was purified by "natural filtration" through soil and sand. However, deep well water was considered less desirable in taste and clarity when compared to rainwater. The development of municipal treatment that filtered and clarified deep well water contributed to the demand by citizens for city water utilities providing drinking water and municipal fire protection.

1897-1954

The city-owned public water and electricity utility was created in 1897 (LUS, 1953, 1954), and both municipal electricity and water services have been continuously provided to the residents of Lafayette by the public utility since that time. The original plant had eight artesian wells placed ten feet apart with depths ranging from 150 to 200 feet (Lafayette Gazette, 1898). The City Engineer, Mr. R. R. Zell (1898), reported to the City Council that the original municipal artesian wells could produce over a million gallons of "good water" per day which exceeded the steam powered water pump capacity. However, by the fall of 1899 only two wells were used by the utility and these two wells had "dried up." The City Council then approved boring a new replacement artesian well to a depth of 200 feet.

Despite the establishment of a municipal water system, by 1900 many of the 3000 Lafayette City residents continued to rely on domestic wells and rainwater cisterns to meet their water needs (page 59, Griffin, 1959). Additionally, deep commercial wells are known to have existed at the railyard and the refinery prior to construction of the municipal water system (Lafayette Gazette, 1895). Based on this, it is reasonable to assert that there are numerous now abandoned domestic and commercial water wells from that early era which were never plugged in a manner that would be required today. These abandoned wells are a conduit that may today be allowing surface contaminants to be drawn into our drinking water aquifer.

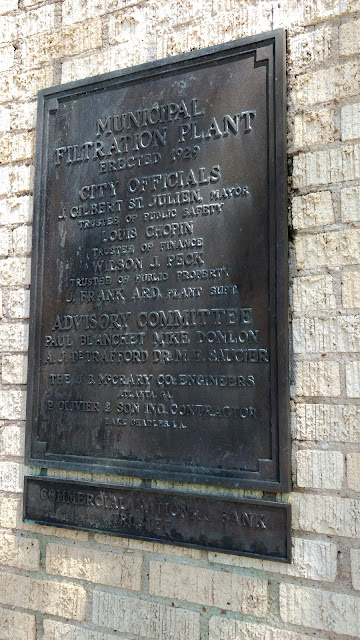

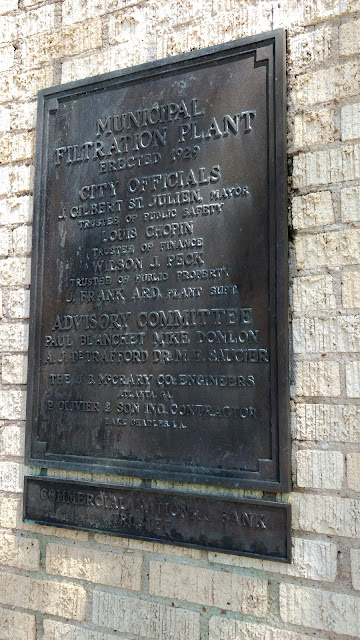

Municipal water systems were not only important for providing domestic and commercial water service, but also significantly contributed to the city's fire protection. In 1902, 1919, and 1928, citizens voted for bond issues which extended the water system and also funded improvements in other municipal services (Griffin, 1959). The North Water Plant building (Municipal Filtration Plant) was constructed in 1929 (Figure 3) with funding from the 1928 bond issue and property taxes. Today that original building is a part of the Lafayette Utilities System (LUS) North Water Treatment Plant facility.

|

Figure 3. Plaque on the North Water Treatment Plant showing that

it was initially erected in 1929.

|

In 1949, the City of Lafayette Board of Trustees adopted a bond resolution for $7,000,000 which funded improvements and extensions to the waterworks plant and the water distribution system, as well as other utility improvement for the electric power and the sewer systems. By October 1952, numerous improvements and extensions were completed or underway (LUS, 1953). The extent of the water system owned and operated by the Utilities System at that time is shown in Figure 4. This map shows the entire water distribution system, including extensions constructed under the bond improvement program. About half of the water distribution network shown in Figure 4 was newly constructed under the 1949 bond improvement program.

Construction of a major plant expansion was started in September, 1952 . This plant extension added two open-type filters, one new

Accelator clarifier (Figure 7) in an existing settling basin, and a new aerator. This expansion also included an extension of the main building to the north for chemical storage and feeding for lime (Figures 5 and 6). Water plant treatment capacity was expanded by 1.5 mgd (million gallons per day) which increased the total treatment capacity of the water plant to 4.5 mgd.

|

| Figure 4. The Lafayette water distribution system in 1952 is mapped in this graphic (LUS, 1953). The water treatment plant is highlighted in red. A 500,000 gallon elevated water tank is to the right of the treatment plant in this map. Fire hydrants are mapped as black dots, 12" mains are mapped as heavier black lines, 4-10" mains are the finer black lines. |

In the early 1950s, water supply for the City of Lafayette was obtained from a system of wells averaging 245 feet in depth in the Upper Sand of the Chicot Aquifer. Part of the wells were located on the filtration plant grounds and part on a nearby separate lot at the intersection of Simcoe and Chestnut Streets (LUS, 1953, 1954). Table 1 shows the location of the five water wells operating in 1952. Wells #1 and #2 were abandoned during that year because of unspecified "difficulties," and a new well was planned at the Simcoe & Chestnut site.

Unit #

|

Location

|

1

|

Simcoe & Chestnut

|

2

|

Simcoe & Chestnut

|

3

|

Filtration Plant Grounds

|

4

|

Filtration Plant Grounds

|

5

|

Filtration Plant Grounds

|

Table 1. LUS water wells in 1952 (LUS, 1953).

The LUS Comprehensive Engineer's Reports (CERs) tell us that the system's water wells drew water from a sand and gravel strata which requires extensive screening at the base of the wells (LUS, 1953, 1954). Operation and maintenance of the wells and pumping equipment was reported to always be somewhat of a problem. It appears that wells loosing productive capacity as the wells aged continued. It was reported that the wells were treated with

Calgon and HT

H (calcium hypochlorite) on an experimental basis resulting in some increase of production. In 1954, wells were constructed fairly close together on the System's properties. However, it was planned that the next new wells might be built on separate property, some 2,000 feet from the treatment plant, where it was expected to have less influence from any of the other wells (this new site may have referred to the site of today's Clark Field and Hebert Golf Course). Water treatment plant expansion in the early 1950s (Figures 5-7) increased capacity from 3.0 million gallons per day (mgd) to 4.5 mgd (LUS, 1954). Difficulties with wells in the Chicot Aquifer Upper Sand, a desire to have higher production, and the recognized need to further separate the well intakes from surface contamination may all have been considerations that led to most of our present day wells being drilled deeper into the Chicot Aquifer Lower Sand.

|

Figure 5. This photo from the 1953 CER shows an expansion of the water treatment

plant building which expanded the original 1929 plant building.

|

|

Figure 6. The expanded water filtration plant (LUS, 1954).

|

|

| Figure 7. Clarifier constructed as a part of plant expansion (LUS, 1954). |

Summary and Conclusions

The Chicot Aquifer has provided a plentiful source of water for millennia, and, if protected, will continue to provide for the water needs of future generations. The Lafayette municipal water system began in the late 1800's. By 1953, Lafayette's municipal water system had expanded to serve 9,247 households and businesses and supplied 825 million gallons of water annually (LUS, 1954). This is 2.26 million gallons per day, or about 240 gallons per customer per day. At that time all of this water was being pumped from the upper sand of the Chicot Aquifer from wells located near the water treatment plant on Buchanan Street at Mudd Avenue.

When the utility began operation at the end of the 19th century, the Chicot Aquifer was a freely flowing artesian water source. This pressure within the aquifer had been protective of the quality of the groundwater from surface contamination because any connections with the surface through springs (Chargois Springs for example), sand inclusions, cracks, abandoned wells, or flow through the confining clay layer itself would flow from the aquifer toward the surface. However, pressure in the Chicot Aquifer has been falling for a century (Borrok, 2016; Borrok and Broussard, 2016).

By 1954 the artesian spring no longer flowed, and pressure had diminished from positive to negative in the Chicot Aquifer. Any hydraulic connection of the aquifer to surface water became a conduit for flow into the aquifer transporting whatever contaminants were present at the surface into our underground drinking water source. Groundwater moves very slowly, often a few feet to a few hundred feet per year. Still, this reversal of groundwater flow direction which took place many decades ago sets the stage for destruction. Recent observations of man made contaminates in Lafayette's drinking water wells (Waldon, 2017a, 2017b) serves to heighten citizens' concerns, and have led to a call for action (Waldon, 2017c).

REFERENCES

Borrok, David M. (2016)

At Your Service: Keeping the Chicot Sustainable, Interview on KPLC TV News, Lake Charles, Published on Dec 21, 2016.

Borrok, David M., and Whitney P. Broussard III (2016)

Long-term geochemical evaluation of the coastal Chicot aquifer system,Louisiana, USA. Journal of Hydrology 533:320-331.

Cheramie, David (2013)

The Legacy of Native Acadiana. Acadiana Profile, August-September 2013.

Griffin, Harry Lewis (1959)

The Attakapas Country: A History of Lafayette Parish, Louisiana.

Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna, Louisiana,

Lafayette Advertiser (1897)

Typhoid Fever and Water Supply. December 18, 1897, page 2.

Lafayette Advertiser (1999)

New well. October 20, page 1

Lafayette Gazette (1895)

Mr. Zell's visit. November 2, 1895, page 3.

Lafayette Gazette (1898)

Water and Light: A model plant nearly completed - Everything works without a hitch. March 5, 1898, page 1.

Lafayette Gazette (1899)

New artesian well. October 21, page 1.

LUS (1953)

Comprehensive Engineering Report as of October 31, 1952. Prepared by R.W. Beck and Associates for the City of Lafayette Louisiana Utilities System.

LUS (1954)

Comprehensive Engineering Report as of October 31, 1953. Prepared by R.W. Beck and Associates for the City of Lafayette Louisiana Utilities System.

Waldon, Michael G. (2017a)

More Evidence of Chicot Aquifer Contamination: USGS Monitoring. ConnectorComments.org

Waldon, Michael G. (2017b)

Contamination of our Chicot Aquifer. What do we know? How do we know? What should be done? ConnectorComments.org

Waldon, Michael G. (2017c)

Citizens seek action to protect our health, property, and drinking water supply. ConnectorComments.org

Zell, R.R. (1898)

Report to the City Council on completion of the Waterworks and Electric Light Plant. Lafayette Gazette, April 16, 1898, page 1.